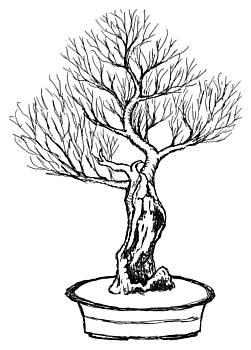

John Naka with his cascading oak at a Nanpukai show

Larger version

John Naka, father of American bonsai, was not only an extraordinary artist but also an avid collector of fabulous trees. Whether digging natives out of local mountains, acquiring garden specimens during landscaping jobs, or rifling through neighborhood nurseries, John found material with masterpiece potential. But John had another avenue for acquiring bonsai: he was the king of barter.

John led a middle-class existence with a back yard full of priceless trees (now the property of grandson Mike). When his collected cascading oak needed to be repotted, he couldn't afford the pot that the tree deserved. However, John's wealth was in his yard, not his wallet, so he said “sayonara” to another of his oaks in exchange for the perfect tokoname pot. His repotted cascading oak now resides in the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum in Washington, D.C.

John most often swapped trees to acquire species not already residing in his yard. Yoshi Sakatani, an early California Bonsai Society member, owned several mountain maples – and John didn't. After a strategic swap, one of Yoshi's show trees, a large specimen with a hollow trunk, found a new home in John's collection.

For several years, the mountain maple was a lush and colorful reminder of the season. With a new front, new pot, and different attitude, John made the hollow-trunk maple his own.

However, as John's final years approached, the maple's health declined. As termite infestation and root rot took their toll, branches died back. When John passed away in 2004, only one branch and part of the apex were alive.

For the next few years, the dieback continued until just one large branch remained. If the tree lived, new branching could be developed – but the trunk wouldn't change. What remained of the hollow, termite-ridden structure was a thin profile when viewed from the original front or back. The side view was wide and taperless.

|

|

|

| Original front with thinner trunk Larger version | Side view showing termite-eaten trunk Larger version |

Although the shape of the trunk was permanent, the front was not. When the tree was rotated, one position showcased the hollow trunk. Not only was there taper and movement, but the flawed portion of the one remaining branch (where it split off into two directions) was strategically hidden behind the dead original apex.

Before repotting, the branch was dramatically reduced in size. Rotted roots and old clay soil near the base of the trunk were washed away. The pot was scrubbed with a bleach solution and thoroughly rinsed before repotting with the new front.

Over the next two years, dieback ceased and the tree thrived. Once the tree was healthy, design became the focus. The remaining branch grew in two directions: horizontally to create a left branch and vertically to create a new trunk and apex. The new growth finally exceeded the height of the old apex. The dead original apex had movement, but lacked the character of the trunk. By carving to reveal termite damage, add taper, and reduce the length, the jin became harmonious with the trunk.

It will take time to develop the new branching. The trunk is large (seven inches wide at the base and seventeen inches tall) and powerful. The new growth needs to have the length and volume to balance the power of the trunk. The eventual height will be approximately forty inches.

One year later, new spring growth has emerged and the tree is beginning to resemble the sketch. More time and more judicious pruning will make the tree show-ready.

Although deciduous trees do not typically have jin or shari, sometimes an exception is worthwhile. John Naka's mountain maple has age and character; with time and trimming, it will become a unique bonsai worthy of display... a trade well made!

[ Top of page | Go back | Go forward | "Trash to Treasure" contents | Site contents | Home | ]