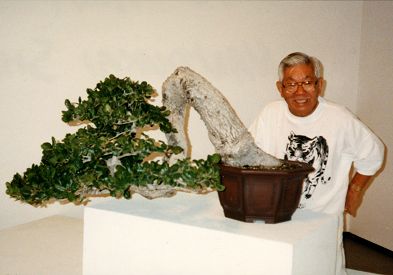

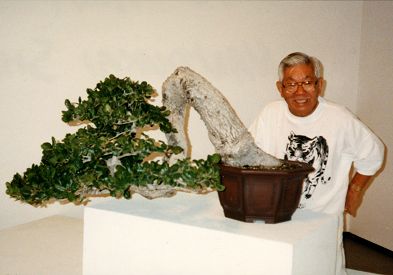

The oak in 1996

Details and larger version

John Naka couldn't help admiring the magnificent oak trees along the 101 freeway and the surrounding hills of central California. Fortunately for John, one of his students, Al Nelson, had permission to collect oak trees near the town of Lompoc. In 1985, Al, John, and Harry Hirao made a number of trips to Bill Darling's ranch. Bill accompanied them twelve miles off the main highway to oak-filled acreage.

John headed west towards the ocean to see trees stunted by the wind, but he found nothing of interest. He then headed for old oak groves and found several trees worth collecting. His eye was caught by one huge oak tree that proudly showed off its struggle to survive. One side was dead; the other was alive, but had no branches near the base. Also, there was no rootage near the soil surface, so it was not suitable for collecting.

However, under the canopy of that large tree grew another oak with an interesting trunk and good rootage. After five hours of careful digging, the tree was his. On that day, he also dug out a second tree that he promptly gave to Marybel Balendonck.

During several trips to central California, John collected six trees. This particular oak was one of John's favorites; even when the apex died and a serious restyle was required, John adored the tree. Over the years, this tree developed a majestic appearance deserving a spectacular pot. John's financial state wouldn't allow such an expenditure – but he was rich with collected oaks, so he decided to sell one of them to pay for a Tokaname pot.

When the John Y. Naka North American Pavilion of Bonsai was built at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C., it was appropriate that a selection of John's trees find a new home there, so he chose some of his most outstanding trees, including the cascading oak.

These trees were gone from his back yard but were never forgotten. John made annual journeys east to visit the bonsai pavilions and the people involved with them. A first stop in the gardens was to visit his four contributions to the museum; he remained involved with their development and design. During each trip, he worked on numerous trees including his own. But with a limited amount of time, much of the work was relegated to the curators of the bonsai collection (Robert Drechsler, Warren Hill, Jack Sustic, and currently Jim Hughes) and their staffs – who cherish these trees as much as John did.

Bonsai is an ever-changing art, but in the early winter of 1999, the oak took a turn for the worse when the apex once again died. The tree was immediately repotted into a larger box. For the next three years, the tree was allowed to go wild and recover. Some of the branches budded back. But the branches that died were left in place as a guide to where the new branching should be placed.

In the spring of 2002, the tree was healthy enough to be repotted back into its original container. When John saw this tree in the spring of 2003, he was pleased to see how much it had recovered. But he remarked that the outline of the foliage was not yet desirable. So John drew a picture of how he would like the new apex to be developed.

Sometimes adversity can be devastating. Other times, it can be a challenge to overcome. In this case, John Naka and the museum's expert caretakers have met the challenge and this oak will soon be restored to its majesty.

[ Top of page | Go back | Go forward | "Profiles in Bonsai" contents | Site contents | Home | ]