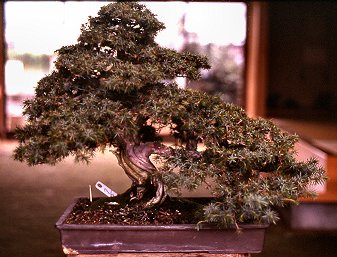

Toshio, before. Larger version

I was not so lucky. A course in advanced hashi would have been helpful. When I was finished, the egg looked as it had gone to battle and lost. It was not a attractive sight. Fortunately, my hashi skills in the workshop were a bit more productive.

As an apprentice in Japan, I've had the privilege to practice many different skills on numerous species of bonsai. The week before I was to finish my first three-month stay in Japan, I was able to apply all my learned skills to one tree.

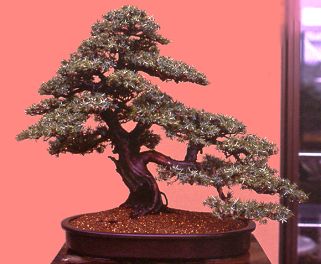

There is a fine bonsai auction in the neighboring city of Hamamatsu on the first Tuesday of every month. In August, Mitsuyasan made the winning bid on a sweet little moyogi (informal upright) toshio (needle juniper). Yochan, my sempai (senior colleague), speculated it had cost about ¥60,000 (about US$510). When restyled and repotted, it might fetch twice that.

Yochan also predicted it was to be my study tree. I informed him that if I were to put my stamp on it, they might find it difficult to give away. However, Mitsuyasan, my brave sensei (teacher), had indeed purchased it for me to practice upon.

The tree was healthy but very overgrown, so my first task was to clean out any aka (dead – literally, "red") foliage and unnecessary branches. Once the initial cleaning was completed, it was time to shape each foliage pad on the branches and create cloud-like masses. The toshio is sensitive to blade cuts, so very sharp hasami (scissors) were called for. I sharpened mine before beginning work on the tree and several times during the procedure. Each piece of foliage was precisely cut to minimize dieback. I made the cleanest cut possible – a flat cut perpendicular to the stem, avoiding the needles.

As is typical of many trees, some of the lower branches were weaker with less dense foliage than the apex and upper branches. Therefore, I was more conservative in trimming some of the lower branches to give the tree more balance.

About half the branches, or portions of branches, were at peculiar angles to the remainder. Copper wire was used to bring these branches into the desired attitude. Only smaller branches were being moved, so gauges 12 to 20 were needed. Some branches were moved only a couple of degrees, but even the tiniest bit of movement made a big difference in the overall picture.

Once Mitsuyasan expressed satisfaction with the styling of the tree, it was time to repot. He chose a shallow oval hachi (pot) to replace the original rectangular pot. I liked his choice since the tree had much movement and would benefit from a softer-looking hachi with curves instead of angles.

The new hachi was prepared for the tree using 18-gauge wire on the screens and 16-gauge wire to anchor the tree. I attacked the root mass by first removing the tree from the rectangular hachi. After the anchor wires were cut from the bottom of the hachi, the tree lifted out with ease. There were many roots, so the rectangular shape of the root mass remained. Using hashi, I then cleaned off the surface soil and swept away the excess dirt with a hoki (brush) and exposed all the nebari (surface roots).

At Mitsuyasan's, they feed and water their trees much more often than I'd been accustomed to. Consequently, many of the fine feeder roots are found near the surface of the soil. So it is essential that the topsoil be replaced periodically.

Once the topsoil was removed, the root pad was placed at a ninety-degree angle to the work table. Almost a third of the bottom rootage was then removed, leaving a flat or slightly concave profile. August is very late in the repotting season, so I took off fewer roots than I would have in the spring.

Hashi were used to clean off all the loose soil and hasami were used to cut all exposed individual roots back to the root pad. Finally, the rectangular edge was combed out with hashi into a softened oval shape that would fit into the new hachi, and the loose roots were trimmed.

A 3/4" layer of hardened, baked, bead-like (3/8 to 1/4" diameter) soil was placed in the bottom of the hachi. This hardened soil (kiryu) is more resistant to breakdown than other growing mediums and therefore perfect as the drainage layer. This is comparable to our use of decomposed granite or lava rock.

A screen mix (80% akadama, 20% kiryu) was slightly mounded in the center of the hachi. The root pad was settled into the soil by gently but purposefully pushing the root pad back and forth just slightly as Yochan held the hachi steady. Hopefully, all the air pockets were removed at this time.

The tree was then tied in tightly. The four anchor wires were secured in a counterclockwise direction that gripped the perimeter of the root pad.

Once the tree was immobilized by the wires, the soil mix was worked into the perimeter, again using hashi. Lastly, a fine layer of soil mix was added to the surface and gently tapped into place with a bonsai trowel.

Immediately upon completion, the tree was thoroughly watered with a fine overhead spray. Even though the soil mix had been screened, there was a good deal of fine dust remaining that was not good for the feeder roots and could clog the drainage screen. To rid the bonsai of this undesirable stuff, the tree was watered until the drainage ran clear.

Finally, the attack of the apprentice upon a poor little tree was complete.

|

|

|

|

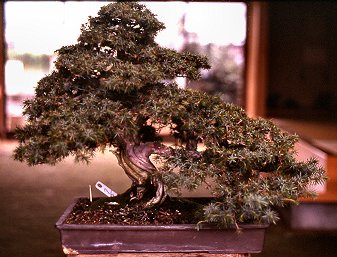

Toshio, after.

Larger version |

Another view.

Larger version |

Postscript: Upon my return to Japan, I looked for this little tree to see if it survived my handiwork, but it was nowhere to be found. Not a good sign. I assumed it had died a quick and painful death, and that Mitsuyasan had wanted to spare me the agony of viewing the awful mess by disposing of it. Luckily, I was wrong. Yochan informed me it had "sold out." What he meant was that it had sold quickly – and was doing well. Yippee!

[ Top of page | Go back | Go forward | "An Apprentice in Japan" contents | Site contents | Home | ]